Roving #1

In this first edition: cat-sitting, gipsies, and biting the hand that feeds you

A monthly collection of morsels, titbits and scraps.

Bring the house down

I get the impression that some people feel sorry for us because we live in a van and think that, given the chance, we would gladly stop being so silly and go back to living in a house, like everyone else.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Whilst there is undoubtedly compromise and hardship that comes with van life, there are many reasons why the idea of living in a house again gives me a severe case of the screaming abdabs.

In no particular order: council tax, energy bills, water rates, rent, mortgage payments, blocked plug holes, scrubbing the shower, mowing the lawn, cleaning the crapper, tidying up, hoovering, heating rooms, washing windows, mopping the floor, tidying the kitchen, loading and unloading the dishwasher, going up and down stairs, neighbours, parking, general house maintenance, boilers on the blink, roof tiles and gales, general clutter and the accumulation of cheap-shit-from-China, stuff in the loft, painting and decorating, the inevitability of Ikea and so on and so forth.

Derbyshire Dave

Derbyshire born, Derbyshire bred, strong int arm, an thick in t’ead.

I am a 45-year-old descendent of agricultural peasants from Derbyshire. I believe my ancestors stood around in barns all day threshing wheat with big sticks until the industrial revolution swallowed them down into the infernal belly of the dark Satanic Mills.1

One slaved away manufacturing screws in Birmingham and the next toiled in a Derby factory producing lamps for railway carriages. His son worked as an iron moulder, also in Derby.

The Second World War intervened on my grandfather’s behalf: he served in Italy and North Africa before returning to Derby to manage a telephone exchange. My own father left our ancestral homelands, then signed The Official Secrets Act 1911 before going to work at the Atomic Weapons Establishment in Aldermaston.

Buried somewhere beneath my southern-softie upbringing in Royal Berkshire are the humble roots of my true kin, the Derbyshire lads.

Whenever I encounter someone with the rhythm and cadence of their gentle, drawling accent, my ears prick up: Ey-up!

So it was that Derbyshire David turned up at the farm-campsite in north-east Scotland where we were staying. I got talking to him when he offered to help my eldest son.

At the age of fifteen, David left school on Friday and went down the coal-mine on Monday.

‘It were quite a shock, I can tell yer.’

He speaks in broad, soft sentences, lilting and friendly, always chirpy, like the canaries he used to carry down the pit.

At the beginning of his first day he was assigned to shadow an experienced man with a pit pony carrying tools and supplies to workers. They went down below and as David passed through the gates, the miners grabbed him, wrestled him to the floor, stripped his trousers off and smeared machine grease all over his bollocks. A ritual welcome.

He later worked at the coal-face in dark, dirty, noisy chambers filled with explosive gases a thousand metres below the surface. It was tough graft, with five to six hours of the shift spent shovelling.

One unfortunate day, so engaged, a section of the exposed surface of the mine collapsed and fell on top of him, smashing up his arm and hand, severing fingers. His workmates managed to get him out and deliver him to hospital, where surgeons stitched his detached digits back on to his hand.

The incident, classed as an act of god, would have seen him go without pay until he could get back to work but his boss bent the rules and got his wages to him throughout his recovery.

‘He saw me right.’

When he returned eight months later, it was in a fire and safety inspection role, as he could no longer handle a shovel effectively after his injuries.

Now retired, he has been reckoning with bladder cancer for some years. When the symptoms first started showing the doctor enquired as to whether he had worked in heavy industry and asked him specifically about coming into contact with formaldehyde.

Formaldehyde, composed of hydrogen, carbon and oxygen, evaporates and becomes a colourless, highly toxic, flammable gas at room temperature. It is used in the production of fertiliser, paper, plywood, and some resins. It is also used as a food preservative and in household products, such as antiseptics, medicines, and cosmetics, and is commonly used as a preservative in medical laboratories, mortuaries, and consumer products, including some hair smoothing and straightening products.

According to David, formaldehyde was used in the pits to inflate huge airbags that would fill the rock cavities above their heads and stop the roof falling in. The chemical was delivered in powder form in sacks which had to be emptied into a giant industrial air pump, sending clouds of dust up in their faces. Once the airbags were in place the men would continue their labour below in a ninety degree Fahrenheit heat while a noxious liquid dripped on them from above.

‘When I told the doctor he said that’s what’s caused the cancer, the formaldehyde.’

The charity MacMillan approached him with an invitation to take part in a new trial for his condition, which he said was a repurposing of a tuberculosis drug that was found to be effective against the cancer cells. It also stripped away the internal lining of his organs but as he told me, ‘it were better than being dead.’

The experience of having cancer, together with the pain and anxiety of the treatment, led to the break up of his marriage.

‘Me wife couldn’t take it.’

Last year, he was ‘absolutely thrilled’ to receive the all clear, and jumped in his car to drive straight up to Scotland, camping in his vehicle, rejoicing and celebrating life in his down-to-earth, cheerful way.

Soon after he bought a caravan and continued his travels, during which time, we met him on ours.

What you’re reading here is my meaningful work, done for wages. You can pay my wages here 👇🏻

Derbyshire Dialect

Utch up!

Move up a bit

It’s gerrin a bit black ower Bill's Motha’s

Black clouds are building up and it looks like rain

Nowt te dow wi’ mey

Nothing to do with me

Let’s be raight’ about this

Let us look truthfully at the situation

But I suppose ‘it’l all come artt in wash me duck

Things will be alright tomorrow love

Shideradtara

She would have had to have

And from my own personal memory archives. Mostly insults:

Yer daft bat!

What a very silly person you are

Yer fat ‘ead

You are a stupid or slow-thinking person with a fat head

Yer great wet lettuce

You clumsy fool

Yer a wazzerk you are

You sir, are an absolute idiot

Stop ear wagging will yer

Please refrain from eavesdropping on our conversation

Cat Sitting in Findhorn

Local customs vary from place to place. Like shifting sands they catch the naive wanderer unawares and as a visitor it’s easy to find yourself flailing around in deep water.

A word of caution then if you ever find yourself in Findhorn on the north-east coast of Scotland and somebody asks you to cat-sit.

You will likely be asked whether you would like to feed their cats while they are away, but beware, this does not mean, as you might reasonably assume, simply feeding their cats while they are away.

What you are being asked to do is engage in a mutually beneficial exchange, which makes perfect sense when fully revealed but isn’t necessarily clear when first proposed.

You will have the use of a residence in a beautiful part of Scotland that, up until recently, was a pilgrimage destination for new-age wanderers and middle-aged, alternative, free-flowing types. The coastline and surrounding scenery is spectacular.

It is considered a benediction to be asked. Consider yourself blessed and prepare to develop a reciprocal relationship with the owners, the house, and indeed the cats.

The nuance to look out for is the way in which the offer is couched in the first place. For example, the Findhorn resident will say something like this:

Would you like to feed our cats while we are away?

(Indicating they are doing you a favour)

Rather than:

Would you be able to feed our cats while we are away?

(Indicating you are doing them a favour)

If, like me, you don’t care for cats anyway2, you might find it somewhat surprising and indeed not a little onerous to end up in a sit-down-cup-of-tea-conversation with the cat owners discussing, amongst other things, the wants, needs and personality traits of the individual cats who live there, their preferred ways of entering and leaving the house, how they like to be approached and talked to and, moreover, how you might contribute to the household bills and running costs during your stay.

The traveller would do well to grasp this local cultural peculiarity before agreeing to something they cannot commit to, or fully comprehend.

The Virgin and the Gipsy

They are drawn to each other by a sublime impulse, a carnal force.

She is naive. She cannot yet fathom what she is drawn to. She flits, childishly, back and forth, as if playing a game.

He is knowing. He understands the depth of what is about to happen. He is a vagabond, sure of himself, radiating sexual authority, toward which, she can orientate herself.

They are archetypes these two, the gipsy and the virgin. Vivid, recurring symbols rising up from the collective unconscious.

She is the beguiling spring maiden of the Spring Equinox, full of potential and promise.

He is the horned god of Beltain, Herne the Hunter, the untameable instinctive wild man of the forest.3

They must consummate, it is a foregone conclusion. How will Lawrence entwine these two with his river of words? What will unite them?

Until now the story has built up tension: will they or won’t they. Each chapter progressively setting the stage for the final coming together without making it clear exactly how it is going to happen, only that it must happen, it must, the tension is almost unbearable.

When the climax is delivered and they are swept together in union, we are carried away on a current of crashing, surging floodwater and cold wind, bruised bleeding limbs, coughing fits, spasms of shivering and blood-stained towels.

She heard somebody shouting, and looked round. Down the path through the larch trees the gipsy was bounding. The gardener, away beyond, was also running. Simultaneously she became aware of a great roar, which, before she could move, accumulated to a vast deafening snarl. The gipsy was gesticulating. She looked round, behind her. And to her horror and amazement, round the bend of the river she saw a shaggy, tawny wave-front of water advancing like a wall of lions. The roaring sound wiped out everything. She was powerless, too amazed and wonder-struck, she wanted to see it. Before she could think twice, it was near, a roaring cliff of water. She almost fainted with horror. She heard the scream of the gipsy, and looked up to see him bounding upon her, his black eyes starting out of his head. 'Run!' he screamed, seizing her arm.

Lawrence, the fourth son of a miner from the midlands, understood this lucid, magnificent, mysterious quality of being human. He could gather it up in words and pitch it hard against brittle convention and stifling, self-imposed, repression. We, the beneficiaries, read open-mouthed as truth and love and desire and courage burst their banks in wild, glorious abandon.

There he stood, naked, towel in hand, petrified.

Yvette, naked, shuddering so much that she was sick, was trying to wipe herself dry.

‘Better lie in the bed,’ he commanded, ‘I want to rub myself.’

…spasms of shivering…

…his black eyes still full of the fire of life…

'Warm me!' she moaned, with chattering teeth. 'Warm me! I shall die of shivering.’

…his body, wrapped round her strange and lithe and powerful, like tentacles, rippled with shuddering as an electric current…

…as it roused, their tortured semi-conscious minds became unconscious, they passed away into sleep.

You might not expect to find such an affirmation of the true human spirit in a church, given that this very institution has spent centuries oppressing its flock and distancing each individual soul from its natural, direct, connection with the divine.

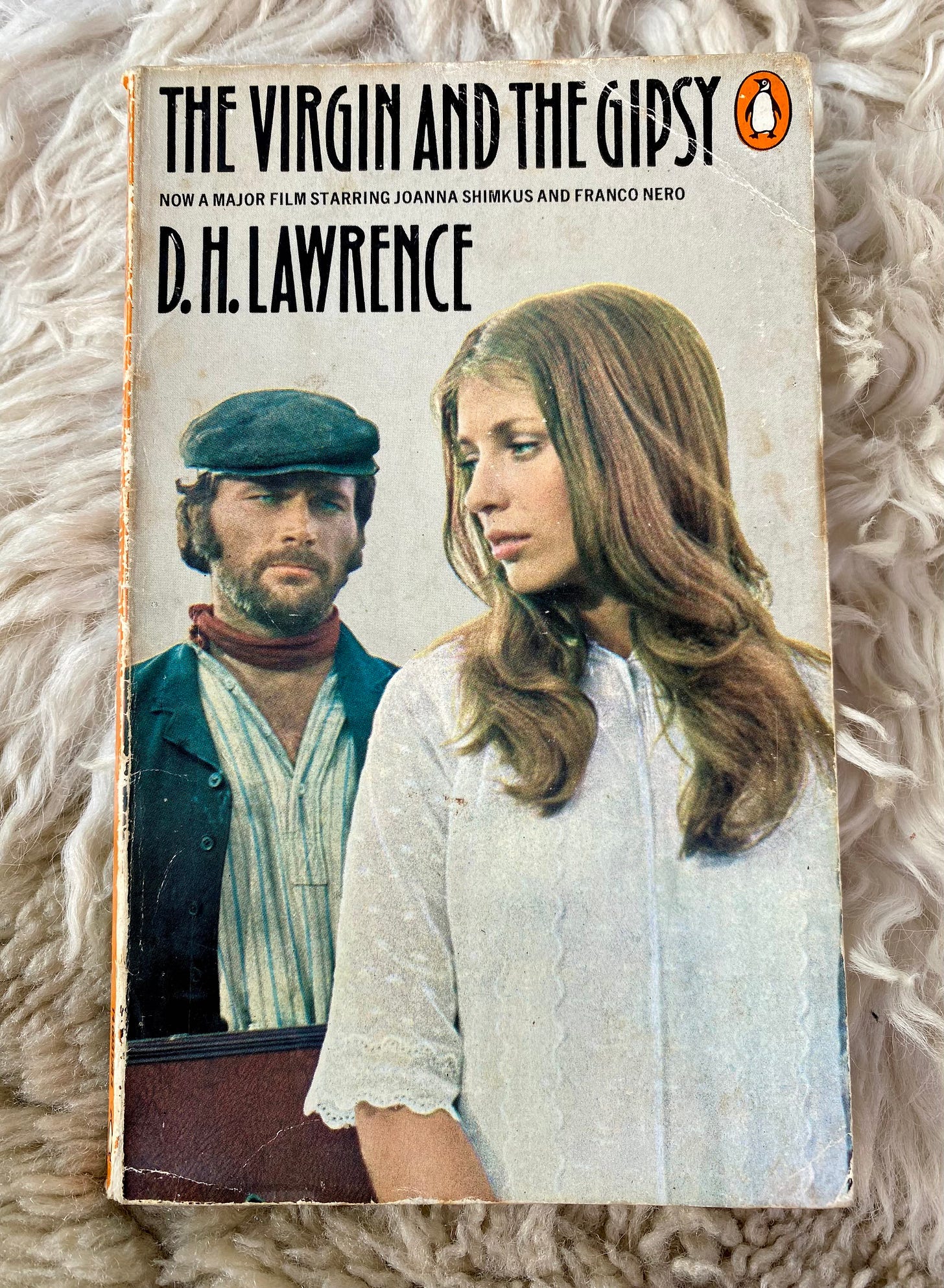

But that is exactly where I found it, all wrapped up in a shabby 1970s Penguin edition with that distinctive orange spine, the print set in Linotype Granjon, the book priced at three shillings.

I walked in to St Andrew’s in Suffolk, a church within a church, on the first day of December last year: the smaller thatched building huddled within the larger ruins of an old Anglican place of worship in the hamlet of Covehithe.

The wooden gates of its vestibule beckoned to me beneath red brick gable and just inside the entrance I found the diminutive library. The Virgin and the Gipsy by D.H. Lawrence was surrounded by a wasteland of literary pap so I rescued it, made the donation box rattle with coins, put the book in my pocket, and left.

Just past the church I walked down the lane bordered by blood-red hawthorn berries toward the edge of the world, where the path crumbles away and falls over the edge of a cliff beset by coastal erosion, eating away the land, making its way slowly, inexorably, toward the old Christian relic.

I work diligently with my pen (or rather laptop) to enrich your day with words; you show your appreciation with money👇🏻

Shake That Man’s Hand

It is mid-morning and I am sitting at a picnic bench with three of my children. We are surrounded by sand dunes and gorse.

Variously, we are whittling sticks, sharpening knives, sanding rust patches on axes, oiling blades and so on. An old fashioned brown suitcase filled with wood tools sits open between us, its contents spilling forth as we dip into it, in search of the whetstone or the Opinel.

We are calm and concentrated, each of us engrossed in what we are doing. Everyone works at their own pace. Subtle learning is taking place. Occasionally there is discreet, deliberate guidance.

A man arrives in his car, parks nearby, gets out and approaches us. He is curious.

‘This looks interesting,’ he says in a Scottish accent, gesturing at the array of tools. ‘What’s going on here?’

‘This is life school,’ I reply directly. ‘I’m teaching them useful things rather than sending them to conventional school.’4

His eyes light up and he begins to enthuse and offer praise, sharing his own thoughts on the subject. This happens to us sometimes.

When he is finished, he says, ‘I want to shake your hand,’ and reaches out his arm.

I reach out in return. We shake hands. He leaves.

Bite the hand that feeds you

I’m grateful to the people who offer me work, because I need it, or rather I need the money I get in exchange, to buy things like food and fuel, and to pay off debts. Without work I would slide into poverty.5

Readers might regard me as someone trying to escape work, and the system that drives it, but the truth is, it is impossible to escape work. Like everyone else, I’m dependent on it, and the society around it, in order to live.

If there is a willingness within to grasp nettles, it is possible to see the reality of things as they really are, rather than how they are presented, make choices based on what is discovered, and refuse certain parts of conventional work-life which make no sense.

An unconventional person can then weave in and out of the system, ducking and diving and skirting the edges. This is what I am doing. I do this for my own sanity, because most work is pointless and the system that compels it is insane.

...if one wanted to crush, to annihilate a man utterly, to inflict on him the most terrible punishments so the most ferocious murderer would shudder at it beforehand, one need only give him work of an absolutely, completely useless and irrational character.6

Italian educator Maria Montessori had a different view.

‘All work is noble; the only ignoble thing is to live without working.’ 7

This is patently not true. Much of the work we do lacks nobility, and indeed moral integrity, excellence, virtue and value.

I’m thankful to the people who offer me work. Nevertheless, much of the work that I do and that is created in our world, is largely pointless, tiresome and soul-destroying.

What is it like to work for forty, fifty, sixty or seventy hours a week turning over five-star hotel beds, turning screws on toasters, trimming cow hides, picking tomatoes, working in an Amazon ‘fulfilment centre’, making pies for M&S, delivering beer for Drizly, sorting recycling bins in Essex, teaching children over the internet, stitching Gap pants in Islamabad, mining sulphur on Java, tiling luxury flats in Rio or working at any productive (making things) or reproductive (taking care of things and people) task in the system? 8

It is possible to see the work clearly for what it is, despise it, and go out and do it anyway. For me, it’s necessary to see things clearly and acknowledge what’s really going on9, to avoid sinking into desperate anguish. Others might counter and say that to face the terrible truth would be too devastating: the final fearful realisation that sends them over the edge into the abyss of the futility of their existence.

Only a madman would convince himself that he is happy doing something utterly futile. Perhaps madness is what is required to do work in this society.

Imagine having to stare yourself down in the bathroom mirror every morning before getting ready to go to work in an Amazon warehouse. Or think of the reality-disassociation one would require to face a day of cold-call telephone sales. How many positive thinking mantras would need to be muttered before putting on a stupid hat and stepping behind the counter in Subway to make long sandwiches. And from where does one summon the will to live, when working in a care home.

Then there is the meaningless grunt-work which I choose over the horrors mentioned above. This toil is connected to the maintenance and repair of all the unsustainable, obsolete objects human beings have misguidedly built over the last few centuries in the pursuit of increased comfort and the fantasy of safety and security.10

The sort of thing I do is paint things that will inevitably need painting again soon, dig holes, fill holes, burn things, kill and remove one set of plants while endlessly trimming and tending to others, move large rocks or small stones from one place to another, carry boxes of possessions from one house to another and clean things that will immediately get dirty again.

Who gives a shit? What a colossal waste of everyone’s time.11

So why do it?

Because like many of you, I am one of the poor ignorant proles. I am not a descendent of the Norman invaders who carved up England for their own benefit at the expense of everyone else, therefore I haven’t inherited land, property, wealth or power.

Unlike the wealthy elite, I must sell myself to earn a living. It is necessary to get money to pay for food, fuel and clothing, goods and services, and Chinese exports. I can choose between dull, alienating work, or poverty.

In an effort not to be poor and immiserated, I moved my family in to a van. We are always exploring ways to reduce our outgoings, by buying less, buying cheap, and mending or doing without.

It’s an ongoing process: not long ago I negotiated my mobile phone bill down to ten pounds a month (with Tara’s help). Am I not clever? But the need for money persists.

Thrift like this is second nature to certain generations of people in this country who can make useful things like furniture and woolly jumpers, fix cars, and save money before spending it.

Unlike them, I grew up in the 1980s when Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher declared there to be no such thing as society and began reorganising the country according to the rules laid out in the neoliberal implementation handbook: weakening the welfare state, cutting taxes, deregulating and setting the market free, commoditising everything, removing the dignity of labour and crushing the unions.12

When I was a child, greed was good. I learnt to consume without saving beforehand, to hit the overdraft, to buy-now-pay-later, or put it on a credit card. Like a good little consumer, with easy access to credit, I became a debt slave.

Right now in the UK the gulf between the rich and the poor13, the flow of middle-class wealth and property to the hyper-rich14, the controlled demolition of the world economy15, and the spread of perpetual emergency, most recently the Ukraine war following hot on the heels of the war on COVID16, ensures that, amongst many other things, we have less money and must therefore take on Bullshit Jobs17.

Myself included: if anyone knows of any bullshit work going, do let me know. All work considered! No job too small! Have soul, will crush it!

The things I currently have to find money for include:

Diesel

Camping gas

Motor insurance, road tax, MOT, service, repairs

Monthly debt payment (van conversion loan)

Basic groceries

Books

Shoes and clothes for the children

Laundrette

The things I no longer have to find money for, thanks to living in a van and cutting back, include:

Council tax (no house)

Rent (no landlord)

Mortgage (no chance)

Electricity bill (solar panels on the van roof)

Heating (log burner/extra jumper)

Firewood (roadside pallet pilfering)

Water rates (outdoor taps in graveyards and petrol stations)

Hot water (only cold water in the van)

House maintenance and repair (again, no house)

Aspirational middle-class high-quality food18 (Lidl)

Netflix, Disney+, Apple TV, Audible, Apple Music, Spotify (Do without)

Holidays and travel (we’re always on holiday and constantly travelling)

The things I have to find money for because I can’t yet tear myself away from the TechnoCore19 include:

Mobile Wi-Fi

Phone tariff

Dropbox

Squarespace

Thoughts? Am I simply a self-indulgent Millennial?20 A financial fuckwit? I recently got pulled up for eating branded Tunnock’s Caramel Wafer Biscuits (£1.59 for a pack of eight) instead of the Lidl clones: Tower Gate Caramel Wafer Bars (£1.35 for a pack of eight). Maybe I’m completely clueless.

I do still eat avocados, but not on toast and not in cafes with exposed brickwork, poured-cement floors and Edison light bulbs hanging from the ceiling, and the last time I bought a flat white was in February.

I’m learning. Perhaps a little late, but I’m learning.

Everything in the Garden is Lovely

I did some futile gardening work for a friend recently. The magpies were squabbling, swifts were screaming overhead. It was hot and sweaty labour.

At the end of the day the owner kindly gave us chives, fennel, lovage and rhubarb, cut fresh from the garden we had tended.

For dinner that evening, Tara chopped the greens into a tuna Niçoise salad with fish, red onion, lettuce, hard-boiled eggs and capers. The next morning she stewed the rhubarb and we spooned it on to granola with yogurt for breakfast.

Both meals tasted so flavoursome and fresh. Mouthwatering.

Perhaps this drudge-work is not so fruitless after all.

Ta very much duck.

If you enjoyed reading my words, please consider sharing them. That’s how I find new readers and earn a living.

If you’ve got something bubbling, consider leaving me a message. I will read and respond to every comment (eventually) and because I’m an adult and not a child I like to engage with opposing ideas, criticism and questions. Having said that, being arrogant and egotistic, I also like compliments.

Jerusalem by William Blake.

I’m allergic to cats (enflamed red-raw eyes, runny nose, constant sneezing, difficulty breathing, chronic asthma, ambulance rides to the hospital to receive emergency ventilation) and yet grew up with four of them in my childhood home. It was the 70s/80s. Things were different back then.

Borrowed from Sacred Earth Celebrations by Glennie Kindred.

Although, increasingly in our society many working people seem to be sliding into debt and despair anyway, despite working all the hours god sends, so perhaps it makes no difference.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky. From The Apocalypedia by Darren Allen.

Maria Montessori, From Childhood to Adolescence

Darren Allen, 33 Myths of the System

Turning labour into a commodity leads to exploitation and alienation; from nature, from society and even from the body. As the system colonises more and more experience, more and more of what we do takes on the alienating and exploitative character of work. This makes people more unhappy, more stressed and more stupid; which generates more opportunities for the market, and therefore more work.

Darren Allen, 33 Myths of the System

The vast majority of doing, acted out by human beings on a regular basis, is done simply to maintain momentum and avoid stopping, and being. Most people, although they would profess otherwise, are terrified of free time, by which I mean extended moments when you are doing absolutely nothing at all, other than being in the present moment (and I’m not talking about meditation here which is just another way to step aside from the central experience of being, although sometimes it might help point us in the right direction). So fearful are we of silence, stillness, inactivity, restfulness, peace and quiet, a formerly natural state of human consciousness, that we have come up with an almost infinite number of ways to avoid it, alter it and fill it with distractions and activity: work being just one example. Why are we so afraid of stopping? Because what waits in the quiet reflective moments is the vast sprawling landscape of the human soul, the deep, dark, untameable truth of who you really are, and the authentic meaning of your life which you have been simultaneously screaming out for and actively ignoring, ever since you were educated out of it as a child.

Alan Partridge

In the UK, the bottom 50% of the population owned less than 5% of wealth in 2021, and the top 10% a staggering 57% (up from 52.5% in 1995). The top 1% alone held 23% (World Inequality Lab, 2022).

Joseph Rowntree Foundation

See Gary Stevenson: garyseconomics

Apart from decent coffee and local honey, two expensive things we haven’t let go of yet.

Read Hyperion by Dan Simmons

Born in 1979, I’m technically Generation X who grew up as a Millennial, but these demographic cohort models serve little purpose anyway.