Each month I share stories of our roving.

Monday 16th December

Trowbridge, Wiltshire

I’m meeting a friend in a cafe to chew the fat. I haven’t seen him for a while. We used to meet here regularly.

The plate-glass windows afford a view over the heart of my old home town Trowbridge: a most-depressing place populated by miserable-looking souls who trudge slowly through the ugly pedestrianised centre past charity shop, betting shop, vape shop, empty shop, repeat. Everyone seems defeated. Life ebbs.

Despite this foul miasma, we enjoy our coffee and conversation, and talk about writing, amongst other things.

He has authored books and encourages me to compose a proposal for my own story and submit it to a publisher. I resolve to give it a go.

Speaking of bad odours, last night we slept on the edge of town near the sewage works. Unsavoury as it sounds, we are not averse to sleeping beside sewage works because they are often quiet, rural places where we can park overnight without being disturbed. It didn’t smell at all bad. Maybe that’s because water companies just dump the sludge straight in to the river these days.

The little River Biss1 up the lane defines the threshold between the water-meadow and main road. Insects dance across it, back and forth. The just-past-full moon, glowing pale pink, is caught up in the spindly bare branches of winter trees. On the roof of the ruined barn in the opposite field, a song thrush shares sweet music.

As we cross the bridge over the Biss and head out of town I feel the now familiar sense of deliverance. Leaving any built up conurbation is always a relief and driving out of Trowbridge is a blessing.

These places we have created to live in, these towns and cities, are profoundly depressing and distressing to the human soul. Living in an unnatural urban sprawl all the time is shit, but it seems fine, because it’s normalised.

To Dartmoor, directly. Let sanity prevail.

Before dark we stop at Berry Pomeroy Castle. As daylight dissolves I discover that we are to spend the night with two phantasmal women: Lady Blue and Lady White, a grief-addled would-be-mother mourning the loss of her baby, and a young woman imprisoned in the dungeons for the crime of being more beautiful than her sister. There’s no sign of them. Not a peep. Just jackdaws on the crumbling walls.

Tuesday 17th December

Berry Pomeroy Castle, Devon

In the morning I dig deep into the soil on the slope behind the van, under the bare trees, while three owls triangulate their calls around me. Gatcombe Brook is down below in the valley and I can hear its silky white sound. It flows on to meet the River Dart west of here. We’re also heading west today.

Seven-thirty seems to be wake-up time for the pheasants, who emerge from the forest, chirping and squawking their raspy koch koch, accompanied by a whirring of wings. There’s some sort of tête-à-tête with an indignant outburst that ruffles feathers. Having laid out their respective arguments, and reached a stalemate, they strut down the hill with chests puffed out, indignant.

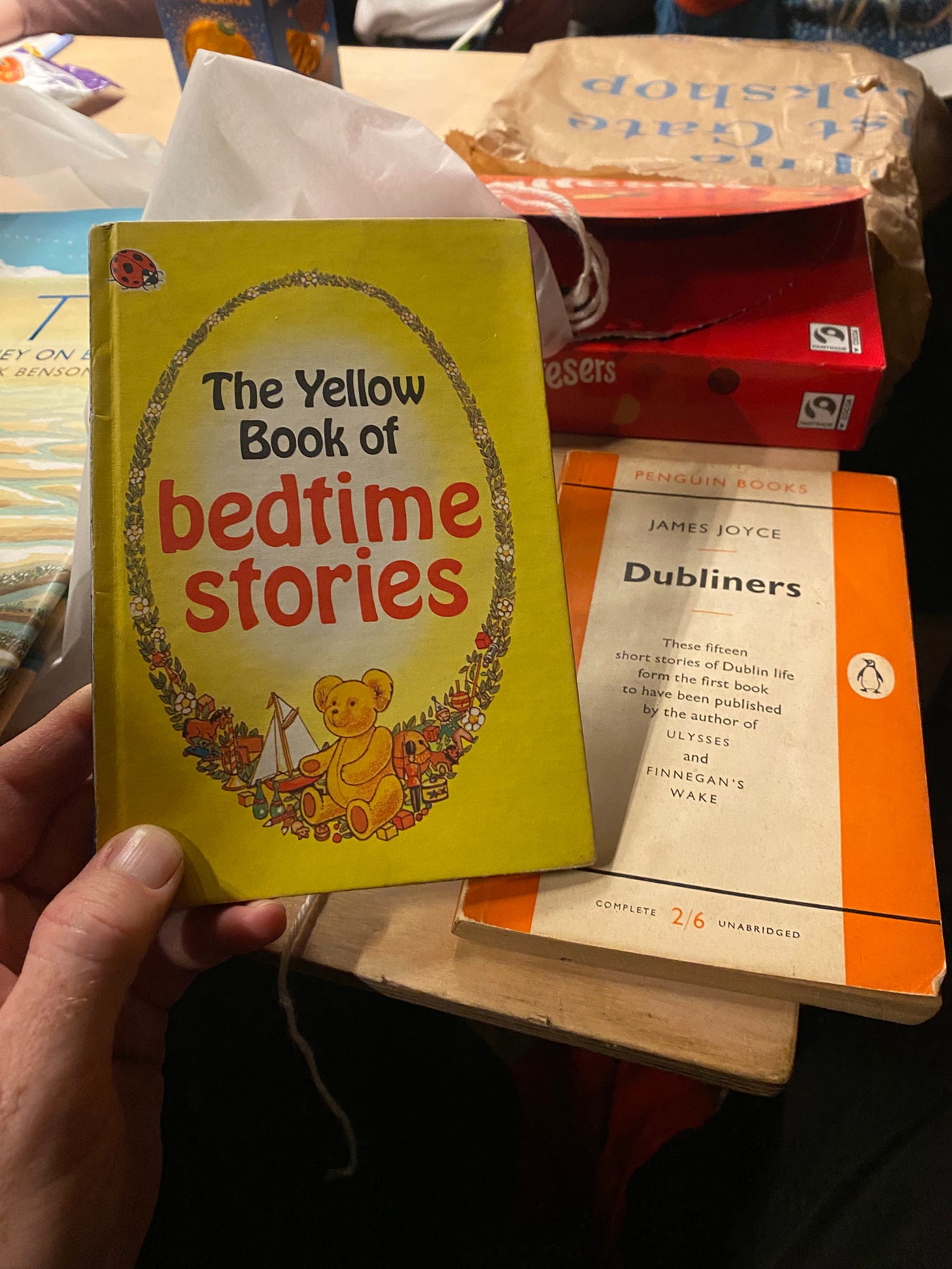

The Dart leads us to Totnes where we want to buy books. Last year we borrowed an Icelandic tradition called Jolabokaflod to supplement our own festive rituals and we plan to celebrate it again in the van on the night before Christmas. Jolabokaflod means Christmas Book Flood and is celebrated on Christmas Eve. Books and chocolate are shared before everyone settles down around the fire to read together.

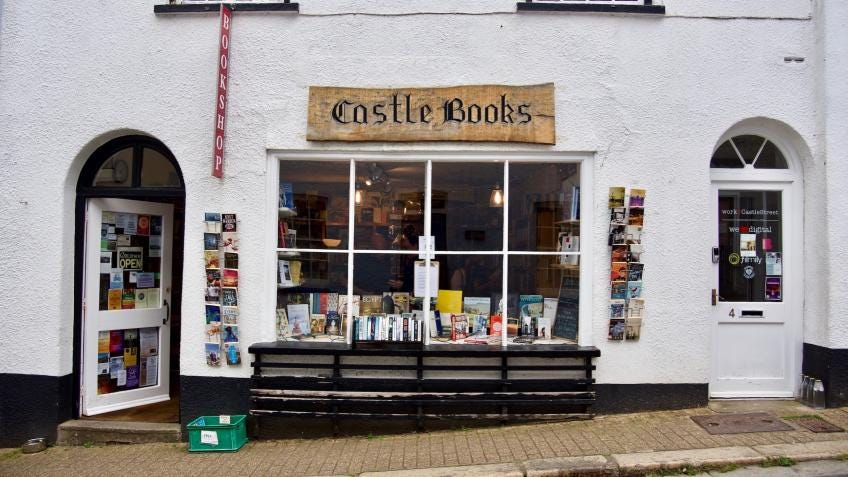

In the town centre we discover Castle Books, a volunteer-run secondhand bookshop tucked away off the main parade in the shadow of a Norman-era castle.

Castle Books is a small frowsty antediluvian sanctuary. The feeling when walking through the door is of a warm embrace face first in the soft bountiful bosom of an old-fashioned aunt. A man sits behind a den-like desk reading. Books are piled around him. He responds to our arrival as if we were guests he forgot were coming.

I find there are few aesthetic and literary pleasures that compare to browsing in a second-hand bookshop. Settling in to the armchair positioned snug in the corner between rising shelves I pick out my Jolabokaflod books: Dubliners and a Ladybird I remember from childhood.

Castle Books started out as a single shelf upstairs in a vegetarian cafe, opened in 1969 by a woman named Belle Collard. More books gathered, as they tend to, and further shelves were added to accommodate them. This continued relentlessly until the food was edged out and the three-storey building became a bookshop in its own right in 1975.

Collard seems to have been an indomitable spirit, good at coming up with solutions to problems. She turned her hand to writing, pottery, farming, property renovation and running a guesthouse while raising her own children at the same time. She persisted with the book business for decades, downsizing to the ground floor in her seventies when the stairs proved too challenging, then continuing with help for another twenty years until she died in 2013, bequeathing her stock of books to her volunteers who established a community interest company to keep things going.

In 2023 with the shop’s lease due to expire and the building up for sale, supporters tried to raise the money to acquire it but the crowd-funding campaign failed. Luckily, a local with deep pockets bought it, refreshed the bookshop’s ten-year lease at below market rent, and offered the volunteers the chance to buy the ground floor in their own time.

This sort of precious story, where goodness and quality are recognised and put front and centre, is rare, and almost has me believing in humanity again.

Wednesday 18th December

Broadhempston Community Woodland, Devon

Dawn. The waning gibbous moon is a halo of light. Mars makes its move, edging close, red contrasting with white. The wind is rushing carelessly through branches like frolicsome children. It is the same wind that rocked the van all night. As daylight trickles in, the moon caresses the rounded breast of the horizon hill and bids goodnight.

Youngest North and his older brother Oak tumble out of the van and we have a three-way synchronised piss just for the fun of it.

The path behind the van, bordered by pine trees, beckons. The ground is strewn with green needles emanating essential oils. The musty, spicy, terpene scent is primeval and North is quite taken with it, inhaling deeply. He hugs a tree trunk by the path in a spontaneous show of thanks.

We continue our climb through the copse, part of Broadhempston Community Woodland in south Devon, and emerge into a clearing called The Beacon, once part of a sixteenth century chain of warning stations: the fire to be lit if the Spanish Armada attempted to invade England. In the Second World War it was used again as a look-out post by the old boys of the local Home Guard who were watching for planes dropping enemy paratroopers.

At dinner time there is darkness and heavy rain. Inside the van, warm and cosy with the log burner roaring, we get into our pyjamas ready for bed. Topless, I flash my capacious chest at Tara. She smirks and mocks my man boobs.

Teasing me, she asks if I have exchanged my youth for wisdom. I say I don’t know about wisdom but my youth is long gone and this is the inevitable consequence of having once had good pecs - eventually they drop.

As it happens I’m in good company. In Greek mythology, this is an experience not unfamiliar to Tiresias, a blind prophet from Thebes:

I Tiresias, though blind, throbbing between two lives,

Old man with wrinkled female breasts, can see…I Tiresias, old man with wrinkled dugs

Perceived the scene, and foretold the rest—2

Thursday 19th December

Dartmoor, Devon

It’s cold. The sort of cold that sharpens the vision. Mars, Regulus and the moon are sitting in the constellation of Cancer, bright as buttons. I gaze at the sky in wonder as my fingers and toes chill. When it gets too much I get into the cab and write until everybody wakes up.

We head back to civilisation for supplies. Bovey Tracey has a brand spanking new Lidl. It’s not two weeks old when we visit. Tasteful wood cladding wraps around the upper half of the giant metal box. A tributary stream leading to the River Bovey is out of sight beyond the edge of the smooth new tarmac in the carpark. Nature has been scraped up and pushed behind the fence: a faux-rustic cleft-split chestnut post-and-rail fence to be precise - an unusual concession to quality and aesthetics by the usually mercenary Lidl overlords.

Inside there are new layers of security: automatic barrier gates glowing green, one at the entrance and another at the exit. It’s necessary to scan your shopping receipt to escape the building. I notice this is becoming more common in supermarkets. It is a Kafkaesque technological nightmare that assumes guilt. What to do about it? Fight back? Boycott? Resist? Fat chance. Suck it up in exchange for cheap groceries more like. Eat mediocre croissants for breakfast and grey tasteless sausages for dinner. You win Lidl.

Next stop is the cemetery, where we have stolen holy water from the outdoor tap once before and plan to do so again. As I pull up in front of the ornate iron gates, a middle-aged woman in an expensive car drives toward me and gesticulates aggressively because I am in her way. I gesticulate back, raising the temperature a bit, and she backs off.

Unfortunately it’s now difficult for me to walk to the tap to get water with any discretion: I will look conspicuous going back and forth between the gravestones with her hanging around. I’m forced to abandon the plan.

A few minutes later, half a mile down the road, another middle-aged woman gesticulates aggressively at me as she crosses the road with her dog. I am at a loss. I have slowed down and stopped to let her pass.

The two women have rankled me and my emotions swell. As we drive I curse them repeatedly, taking the Lord’s name in vain, and blackening their characters using a favourite fourteenth century obscenity from The Miller’s Tale.3

To escape the aggravation we head to Haytor Rocks and Haytor Lowman up on the moor. There is a biting wind and fearsome hail that stings the face. The weather is rolling over in phases. It’s a short walk to the rocks so we all get out and head up the hill during a calm period, sheltering behind the bulk of the imposing granite when the hail inevitably returns. As I crouch in the alcove with my daughter Red I think of the generations of people who may also have taken shelter here over four-thousand years on prehistoric Dartmoor.4

Sunshine breaks out and we clamber higher on the rocks. The wind is bitter so we drop down and huddle together halfway up Lowman to range with our eyes across this capricious landscape which changes its mood on a whim.

After descending we drive to Hound Tor, make lunch, and then move again to settle for the evening under a starlit sky at Bonehill Rocks - that’s four tors in one day.

Visiting a series of hill tops such as the Munros of Scotland or the Wainwright Fells of the Lake District has always been a popular sport and Dartmoor’s smaller rocky peaks are now the focus of ‘Tor Bagging’, which has proliferated in recent years, perhaps fuelled by the march on the countryside by the townie masses during the pernicious lockdowns. Tors are now being bagged more regularly than ever before, the experiences shared on unsocial media, encouraging others to do the same.

I am dismissive of such notions. It seems to me to be driven by the acquisitive mindset of the consumer, responsible for the commodification of everything, including nature, with the result that the sacred is stripped out, and the majesty of these high craggy hills, which require prolonged periods of quiet observation just to comprehend their awesome physical formation, let alone their mystical beauty, become profane commodities.

If you cannot avoid being avaricious in nature, send a stamped addressed envelope to the Cornwall and Devon Long Distance Walkers Association and you will receive in return a list of two-hundred-and-eighty-three Dartmoor tors to procure at your leisure.5 Or better still, stay away. Try shops instead.

The rocks at Bonehill are piled up and riven with crannies. The boulders tumble on top of each other to form fat stacks which, when crested, cast views over the East Webburn River and Widecombe in the Moor.

Standing outside in the deepening dark at the mercy of the cold cold wind I regard the shadowy outline of the bulky granite, crouching ominously on the skyline like an animal.

It came with the wind through the silence of the night, a long, deep mutter, then a rising howl, and then the sad moan in which it died away. Again and again it sounded, the whole air throbbing with it, strident, wild and menacing.6

Friday 20th December

Dartmoor, Devon

In the morning as the first light comes in, orange pink and yellow fuse and flare in the east. On a nearby stone, crow contemplates the day.

At this time in the morning the rising sun paints the sky in shades not seen later. Fresh brushstrokes alter the canvas from moment to moment. It’s an auspicious time, easy to miss, and sometimes the jealous clouds hide the whole show, but those who rise early, without expectation, often receive rich reward.

Below me, a pretty maiden makes her way up to the rocks, walking two dogs. I give up my claim and make way for her. She sits on an outcrop and watches the sunrise. At a distance, I stand and watch too.

After breakfast pancakes Thor and Oak climb the rocks and Thor slips and falls off, walking away with bruises but bones intact.

We have to go back to Bovey Tracey and come in from a different direction, driving down the hill to be greeted by Dartmoor Whisky Distillery.

After parking in town it draws us back up the hill and since the door is open, we poke our heads in.

In a large vaulted room with a wooden floor, filled with tables in front of a raised stage, the owner is refilling the fridge behind the bar.

It’s mid-morning and he tells us he’s not open until the evening when singer Seth Lakeman is playing a private charity gig. We confess our desire to try some of his whisky and he graciously accommodates us with a flight of expressions: three drams and a shot of gin. The whisky is good but the botanically fragrant gin is outstanding. It’s all made in an antique ex-cognac copper still7 which was manufactured in France in 1890 and now sits proudly behind the stage, dominating the room.

At some point during the tasting it has been decided in Tara’s mind that we are going to spend our combined Christmas money on one bottle of this fine fellow’s water of life and he sends us to the shop next door to make the investment.

Looking back with the bottle long since drained, I must say that it was not worth the price-tag. It had a lovely smell and initial taste but was hard in the mouth and had a dry finish with a harsh aftertaste. It needed water to make it palatable.

The best I’ve tasted is the 12-Year Whisky we picked up from the Tobermory Distillery on the Isle of Mull in February last year - for less than half the price of the Dartmoor bottle.8

Saturday 21st December

Dartmoor, Devon

It is winter solstice, the beginning of astronomical winter, and the first day of Yule: rainy, breezy, but mild.

Eldest, Thor, is turning the pages of our old family Christmas-Yuletide folder, looking at pictures from the past and reading what we got up to in years gone by.

He reminds us that on this day in 2019 we went to Green Lane Wood in Trowbridge to look for evergreens. Tara found holly and then stumbled across the windfall branch that was to become our first yule log. Thor chopped it in half with an axe and we carried it home, beginning a new family tradition.

Today we are looking for yule log 2024.

Yule is one of the oldest winter solstice festivals, pre-Christian, and probably originated in Scandinavia before being subsumed, along with other pagan traditions, into the Christmastime celebrations.

I have been rummaging through folklore for years looking for meaningful rituals. The yule log tradition is still popular today albeit in a variety of altered forms. The old stories say the original was a large log that burned throughout the twelve-day festival.

This is traditionally a log of oak, a sacred tree with connections to the Sun king. It is a very slow burning wood that gives out great heat. Traditionally it was placed on the fire with much ceremony, and the ashes were kept for fertility rituals.9

As we don’t live in a viking mead hall with a large central fire pit (more’s the pity), we don’t place our limb on the fire but on the table instead where, adorned with evergreens and twelve candles, it makes for a fine centrepiece.

Last year was our first Christmas in the van and we didn’t have a log because there wasn’t any space but this year we are determined to find a way to bring the tradition back. We’re looking for something just right.

Robin redbreast perches amidst the twisted ivy on a broken birch branch as we march down the track in single file to Pullabrook Woods, armed with chopping tools.

Once we are over the barbed wire fence everyone scatters to begin the search. There are plenty of fallen trees lying around. Tools in the hands of children are put to work very quickly and the chopping and sawing begins almost immediately without much focus. Oak helps his little brother and sister to cut their own small log with our handy Opinel No.18 Folding Saw.

Eldest Thor is more self-sufficient and exacting. He has a perfect idea in his head which isn’t being met by reality, much to his frustration. I invite him to relax into the vibe of the surroundings and see what the trees have to offer, but he ignores me. Tara is off looking for evergreens, gently peeling a coil of climbing ivy from a tree trunk.

It becomes apparent that everyone wants their own log this year and we trek back up the hill later with four small pieces, each a different shape.

Christmas songs fill the van as Tara makes a garland from the evergreens she has gathered and I help the children drill candle holes in their logs.

Later we return to Bonehill Rocks for the evening where there is a fierce wind gusting. Thor climbs the stone stack and falls off again, adding scrapes to bruises, but still no broken bones.

Back in the van the scent of mulled wine permeates. The children are wrapping presents at the table and we give strength to the sun king by lighting the first candle on Thor’s yule log.

Sunday 22nd December

Dartmoor, Devon

A promising pancake breakfast results in miserable conflict with youngest North about how much butter and maple syrup to put on (so as not to leave any waste). I respond unskilfully to his musk ox defiance10 and ramp up my bull energy to see off the young challenger. This makes me feel wretched and puts me in a foul despairing mood which I fail to resolve. Regrettably the emotional swirl swamps me and I withdraw to the front where I sit with my head in my hands. Not my finest hour, and not the first time this has happened. It won’t be the last.

Respite comes later in the afternoon at Soussons Cairn Circle near the heart of Dartmoor. The dark is rising, enveloping the surrounding moorland before swallowing the van. Inside we counterbalance, setting the log burner to work and lighting the second candle.

Monday 23rd December

Dartmoor, Devon

Dartmoor has a cold heart this morning but the wind has dropped so the chill isn’t biting. Jupiter was supremely bright last night and Mars is still glowing red behind the silhouetted pines when I wake.

Dawn is warming up in the east: blue-yellow hues. Half moon is crystal clear. There is a stillness in this place. It knows itself.

The stone circle calls. I circumnavigate, then enter. There is an offering of flowers tucked under a nook. Evidence of fires lit in the centre has me conflicted. On one hand, this is a scheduled monument and a precious archeological site. On the other, gathering around a bonfire at the centre of a stone circle feels like the most natural thing.

It is the absence of a lived primal relationship with the land, and the administrative documenting, cataloguing and abstracting of our natural history (which strips it of its sacred nature) that is disconnecting us from the earth and each other and contributing to our separation and devastation.

Of course, I then look up just such an administrative document11 to find out more about the ground beneath my feet and I have to admit, what I read does enhance my experience of the place.

The twenty-two stones, none over knee-height, define a twenty-eight foot diameter circle which is described as sepulchral because of what was found at its centre: a box-shaped burial chamber made from stone slabs, known as a cist or kistvaen.

When it was revealed the cover stone was gone, but side stones of thin, shapely slabs remained and the rocks at the bottom concealed a secret. Beneath them, in the true bottom of the kistvaen, there was a cavity containing two large coils of human hair.

An account of the find, together with some of the hair, was sent up the administrative chain of expertise to a Mr F. T. Elworthy, who concluded:

I think there is no sort of doubt that the deposit was made in comparatively modern times relatively to the kistvaen by some-one who knew of the latter and desired to work a spell on the former possessor of the hair. I have referred to the belief that sympathetic magic can be worked by the possession of any article (especially hair) that belonged to a person to whom it is desired to work evil in my book The Evil Eye.

Since writing that I have much more evidence. In Italy it is a well-known rule to avoid leaving in any place any particle of hair, because if it falls under a witch's eye a curse is sure to follow you. The intention in your deposit was that as the hair was buried and pressed down under flat stones, so the owner of that hair might be caused to pine away and die. You have lighted on a true witch's piece of work which had no sort of connection with the prehistoric interment.

Throughout the day, dark magic seeps in to my consciousness, and that night I have wicked dreams about men of violence cutting and wounding with knives. Is this the malevolent story of the stones?

In another dreamscape, someone sets a good hearty fire at the centre of the circle. Gathering in close, young and old sing and dance hand in hand around the flames until they are dizzy, then leap the inferno with wild whoops. In doing so, they set ablaze the nefarious nature of literal man’s dark soul and, with joyous primal truth, set the world alight.

Thank you for reading my work. I’ve turned off Likes and Comments but I enjoy hearing from you so if you have any thoughts, send a Message and I will read and reply.

If you become a Paid Subscriber the app will give you three choices:

Monthly Subscriber £5

Annual Subscriber £50

Founding Subscriber £250

If you remain a Free Subscriber do consider dropping me a supportive tenner now and then, via PayPal or Stripe.

Swedish academic and scholar of English Language Eilert Ekwall suggests Biss is Brittonic, from the reconstructed word bissi, cognate with Welsh bys and Cornish bis, literally meaning finger with the transferred sense of river fork.

The River Biss is therefore the River River Fork.

The Biss is a tributary of the River Avon, a word loaned from the Brittonic abona, meaning river, which survives in the Welsh word afon.

The River Avon is therefore the River River.

Ergo, if the River Biss is the River River Fork, and the River Avon is the River River, then the River River Fork is a fork of the River River, clearly.

The Wasteland by T. S. Eliot (1922).

Cunt, or rather ‘queinte’: The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer (1387-1400).

The remains of prehistoric round houses, field boundaries and burial cairns, bear witness to the presence of our ancestors. Ten-thousand years ago people were visiting Dartmoor to hunt, but it wasn’t until about four-thousand-five-hundred years ago that folk began to settle down in large numbers, to farm the land.

The Hound of the Baskervilles by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1902) is set against Dartmoor's dark and brooding landscape.

A still is a giant copper kettle. During distillation of whisky, the still is heated to just below the boiling point of water and the alcohol and other compounds in the liquid (usually a mixture of barley, water and yeast) vaporise and pass over the neck of the still into either a condenser or a worm – a large copper coil immersed in cold running water where the vapour is condensed into a liquid. After being distilled the liquid is moved to mature in oak casks.

I am, I have to confess, rather a rank amateur on these matters.

Sacred Earth Celebrations (Second Edition) by Glennie Kindred (2014).

Musk ox defiance: