Book of Travels: February

Red kites, icy peaks, and full-bodied pirates in Wales.

Each month I share stories from a week of our roving.

Monday 17th February

Gospel Pass, near Hay-on-Wye, Wales

When I wake, there is ice on the inside of the windscreen. It’s blowy and cold outside. Walking into the wind toward gorse bushes my hands go numb and I seek shelter in a shallow dip. It’s difficult to dig deep with frozen fingers but I keep at it with the pick and get down six inches before squatting. A red kite rises up to meet the descending moon and noses into the fierce gusts, hovering high, holding steady. Forked tail pivots.

Afterwards, I go back and saw lengths of pallet wood to feed the fire that will warm the van from within. The wind carries the sawdust away before it hits the ground.

We’re parked in a long lay-by on Gospel Pass, a narrow lane which meanders over the Black Mountains1 in South Wales between Abergavenny and Hay-on-Wye (via the nine-hundred-year-old ruins of Llanthony Priory). At one-thousand-eight-hundred-and-one feet, it is the highest length of road in Wales. Its name harks back to the medieval monks who used it to spread the Christian gospel.

Last night a rented camper van rolled up and pulled in. After many minutes of indecisive manoeuvres it parked alongside. This morning a man, Mike, emerges and comes over to say hello. He has an estuary accent. He is wearing a onesie. His face is friendly and open so I decide to forgive him his ridiculous attire and lean into the conversation as the cold wind whips between us. He picks my brains about van logistics. Behind him, I can see his wife hiding from the weather in the cab. She looks like she is out of her comfort zone. Mike tells me she is worried about the wind - last night she wanted to abandon the trip and drive home.

They had initially parked side-on to the wind and sat inside with growing alarm as it was buffeted back and forth, which, as I know only too well having been on the receiving end of many storms now, is rather unnerving. It feels like being rocked roughly in a crib by a revengeful older sibling.

We were both awake when, in the middle of the night, the gale suddenly stopped and everything became calm. It didn’t last long and the gusts continue to batter us now. Mike looks cold in his onesie so I wind up our chat and wish him well.

The wild weather looks set to stick around. Rather than battle up into the hills we decide to return to Hay-on-Wye and shelter in cosy bookshops. We did the same thing yesterday and on Tara’s recommendation I got lost for hours in Hay Cinema Bookshop, on Castle Street, which opened in 1965. It contains a treasure trove of titles laid out on far reaching shelves extending into the distance in the large basement and first floor.

When I enter, an old crone with a wart on her face looks up from the book she is reading behind the front desk. Beside her stands a pretty maid dressed in expressive feminine colours, prints and layers. There is a slight resemblance between them in bone structure and facial features and I wonder if they are mother and daughter. This has me reflecting on the toll of time: the effortless natural beauty of youth, and the loss of this lustre in later years. The old woman has gained something since she surrendered hers. Although the younger girl catches the eye, it is the older who commands the attention.

I descend into the musty depths and forage a few penguin classics with orange spines, then get a little light-headed when I discover a nook with two or three shelves brimful of old Ladybird books.

Henry Wills and William Hepworth printed and published the first Ladybird imprint in 1914 at their premises in Loughborough, Leicestershire. The pocket-sized hardback familiar to many of us measures roughly four-and-a-half by seven inches and used a fifty-six page format because a complete book could be printed on one large standard sheet of paper, folded, and cut to size, without waste. This meant the books could be sold at a low price which, for almost thirty years, remained at two shillings and sixpence (twelve-and-a-half pence).

One of my favourites so far is The Story of Oil by W. D. Siddle with illustrations by Robert Ayton (1968) which ‘tells the story of oil from its formation in pre-historic times to the present day when it is so drastically changing our lives and surroundings’.

That introduction, which recognises the drastic impact of oil, was written in 1968. God knows how the writer would describe the impact of oil today. On page twelve there is a detail about petrol which is quite incredible to think about:

For many years the chief product from the early refineries was lamp oil, so called because it was burned in oil lamps. Great Britain was among the countries to which lamp oil was exported. Enterprising salesmen toured the streets of London, and other large cities, in horse drawn carts, carrying tanks of oil which they sold by the gallon. By 1900, lamp oil was so popular that over one hundred million gallons of it were being sold in Great Britain alone every year.

Another, more inflammable, liquid was produced by distillation of crude oil. Sometimes separation of this liquid from lamp oil was not complete, and the oil exploded when it was lighted in a lamp. There appeared to be no commercial use for this liquid, and the usual way of getting rid of it was to pour it into open pits and burn it. This liquid was petrol, for which there was then no use!

Petrol, was burned, in pits, because there was no use for it. Staggering.

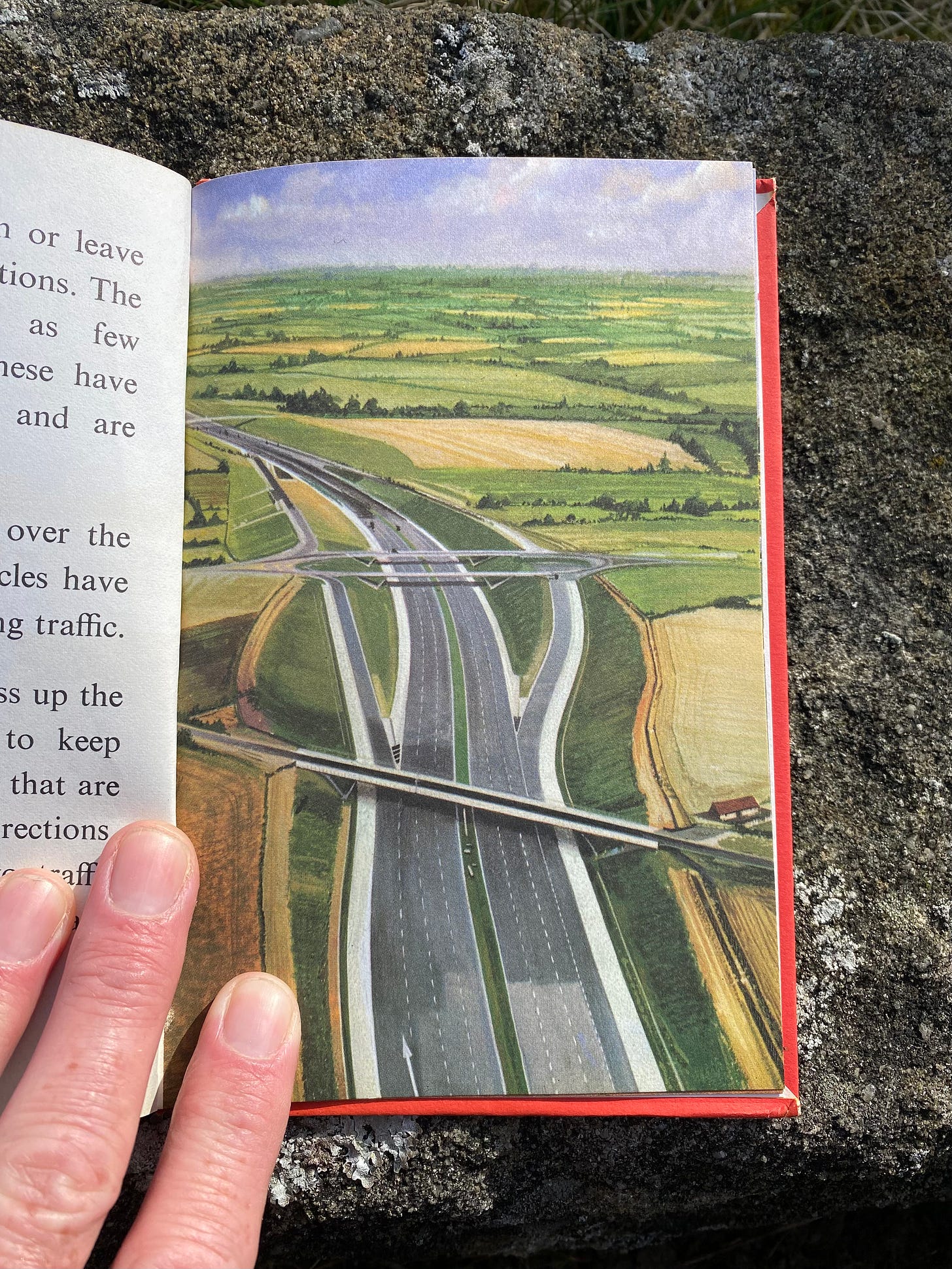

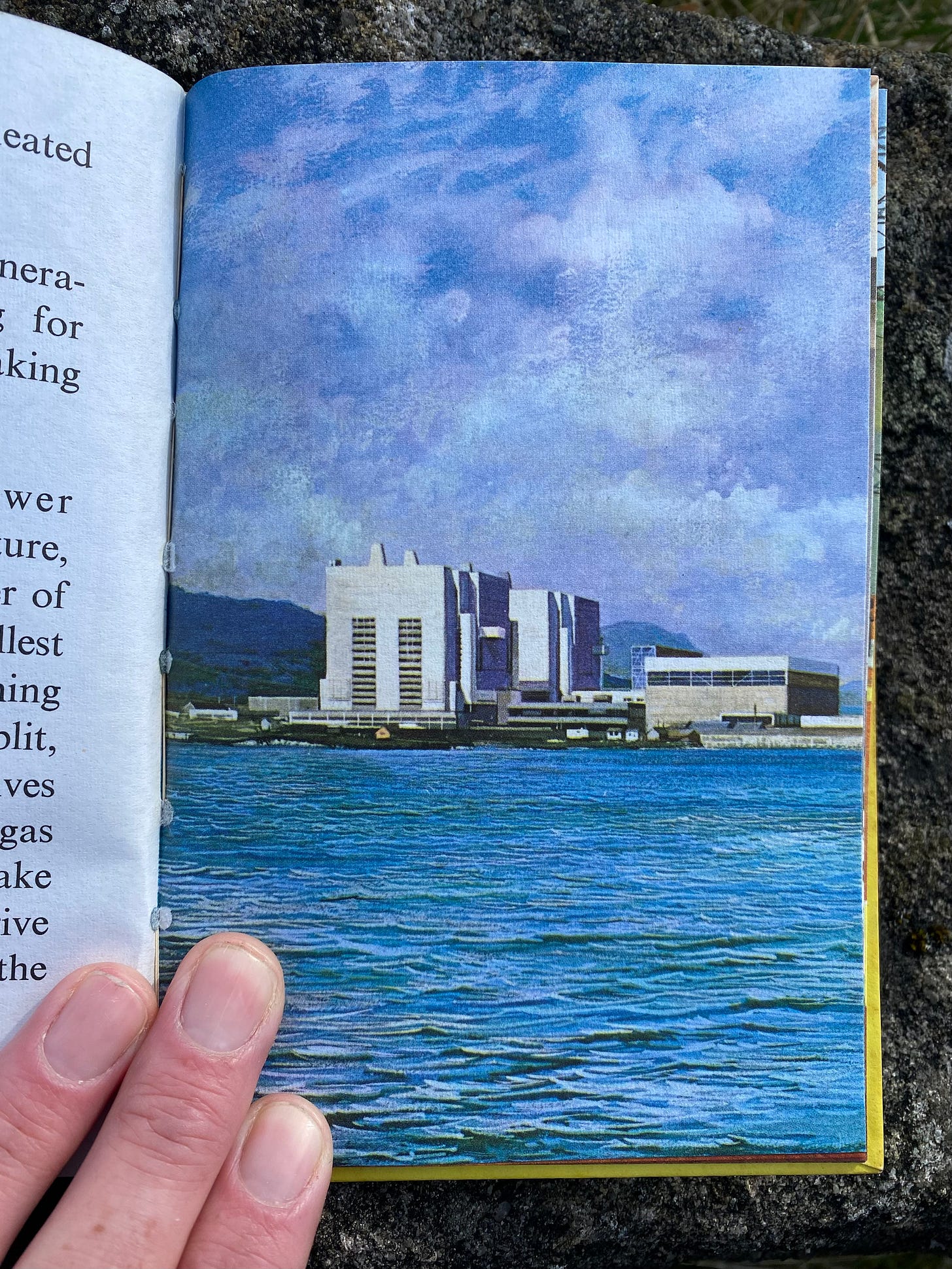

These Ladybird books were written fifty years ago when the future looked bright, modern, clean and clever. For example, here’s a beautiful motorway and a picturesque nuclear reactor. I think you’ll agree it all looks absolutely charming.

Sad to reflect on how it all turned out.

Although written for children, Ladybird books are not patronising or silly. They are written in clear, concise, considered prose, far superior to the equivalent AI mash-up an online search provides.

Driving on, we sight two red kites, then two more. Suddenly there are kites everywhere. This seems odd, something is afoot. A cluster of birds is gathering over a residential area and we head toward the epicentre, arriving outside a house in Talgarth, Powys, where, we discover later, a retired butcher in his eighties feeds them twice a day with chunks of meat thrown into his back garden.

The once endangered birds, which were previously close to extinction in Wales, flock for the leftovers, swooping in with outstretched talons to score the scraps. We seem to have arrived at the end of the afternoon session and there must be thirty kites in the air. We watch the birds circle and dissipate as the feeding frenzy dies down.

We are also hunting: we need water and wood, which in practice means visiting cemeteries (where there is often a tap for watering the graveside flowers) and business estates (where we might chance upon put-aside pallets). Mostly we find what we need as we go along, taking opportunities as they arise, without the need for significant detours, but sometimes, like today, we run out of water and wood and must find some directly.

If you’re sitting in the conventional seats, I expect it is hard to imagine spending part of your day going in search of drinking water or fuel. After all, water, fuel, and other essentials are laid on for convenience in your house (as the household bills reflect) and you probably don’t put too much thought into sourcing them.

This modern situation frees up time for you to go ahead and lead your life, which if I remember rightly from my own past experience involves going to work most days (to pay for the essentials), and cramming everything else into ‘free’ evenings and weekends, including leisure (which requires extra money).

Like many people I view this traditional five-day work model as rather topsy turvy, not to mention unnatural, limited, and unfulfilling but, embedded within the system as most of us are, it is difficult to break the habit, let go of the convenience, and seek out a different rhythm - something more akin to human being, rather than human doing.

A few of the best of us have managed to push to the edges in an attempt to break free: writers and artists like Thoreau or Gaugin for example,2 but most of us choose to live a life of comfort, security and convenience, even if it is a form of incarceration.

When you live in a house where everything is provided, something important is missing, something that is at the root of our misery and unhappiness in the modern world.

The work of finding essentials (water, food, fuel, shelter) is woven into our collective soul. Carrying it out successfully satisfies our psychology and spirit at a core level.

The purposeful work of securing essentials is no longer possible because the land and its bounty have been closed off, industrialised, privatised, and commercialised. Instead, we now spend most of our time doing hollow, meaningless, dispiriting work, that leaves us feeling worried and wretched. I know this from previous experience.

Our hunt for water and wood is successful. After some time, we find a churchyard tap and a large pallet in the far corner of an industrial estate. I now know that my body will be warmed and watered. A settling takes place. There is a feeling of achievement and modest success. It is temporary and I know I will need to embark on the search again in a few days, but each time I find the water and the wood, I am reassured that the earth is bountiful and plentiful. The work of finding essentials for life is existentially rewarding and deeply satisfying.

You might point out that I have stolen both the water and the wood from private owners, and you might add that neither has been foraged naturally, and you’d be right. My ability to gather (clean) water from streams and rivers, and harvest kindling and firewood from the land has been severely restricted, or made impossible, by historical expulsion from the commons, enclosure, industrial pollution, private ownership and all the other trappings of modern life which we call progress. I steal from the system that stole the resources in the first place.

Ted Kaczynski highlighted the devastating impact of technological progress, and the importance of working to gather essentials, in his manifesto Industrial Society And Its Future published in the The Washington Post in 1995.3

Kaczynski pointed out the disastrous effects of progress on the human race.

The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race. They have greatly increased the life-expectancy of those of us who live in “advanced” countries, but they have destabilized society, have made life unfulfilling, have subjected human beings to indignities, have led to widespread psychological suffering (in the Third World to physical suffering as well) and have inflicted severe damage on the natural world. The continued development of technology will worsen the situation. It will certainly subject human beings to greater indignities and inflict greater damage on the natural world, it will probably lead to greater social disruption and psychological suffering, and it may lead to increased physical suffering even in “advanced” countries.

The industrial-technological system may survive or it may break down. If it survives, it MAY eventually achieve a low level of physical and psychological suffering, but only after passing through a long and very painful period of adjustment and only at the cost of permanently reducing human beings and many other living organisms to engineered products and mere cogs in the social machine. Furthermore, if the system survives, the consequences will be inevitable: There is no way of reforming or modifying the system so as to prevent it from depriving people of dignity and autonomy.4

Kaczynski advocated a more simple way of life. He suggested that human beings need to feel autonomy through having a goal, directing effort toward the goal, and achieving some success.

When the goal is obtaining the physical necessities of life: food, water, clothing, and shelter, there is a deep and satisfying reward, not least because these goals correlate with survival - failure to achieve them may result in death.

But, as Kaczynski points out ‘…the leisured aristocrat obtains these things without effort. Hence his boredom and demoralization.’

Consider the hypothetical case of a man who can have anything he wants just by wishing for it. Such a man has power, but he will develop serious psychological problems. At first he will have a lot of fun, but by and by he will become acutely bored and demoralized. Eventually he may become clinically depressed.

…

But not every leisured aristocrat becomes bored and demoralized. For example, the emperor Hirohito, instead of sinking into decadent hedonism, devoted himself to marine biology, a field in which he became distinguished. When people do not have to exert themselves to satisfy their physical needs they often set up artificial goals for themselves.

Kaczynski then goes on to describe an artificial goal, or surrogate activity:

Here is a rule of thumb for the identification of surrogate activities. Given a person who devotes much time and energy to the pursuit of goal X, ask yourself this: If he had to devote most of his time and energy to satisfying his biological needs, and if that effort required him to use his physical and mental faculties in a varied and interesting way, would he feel seriously deprived because he did not attain goal X? If the answer is no, then the person’s pursuit of goal X is a surrogate activity.

When I look around, it seems to me that almost everything people are doing in the modern world is surrogate, rather than essential, which, if true, makes for a lot of bored and demoralised people, and consequently, a sick society.

Intrinsic to the work of finding essentials is being in nature.

Finding water, food, fuel, shelter, means being close to nature: living within it, being part of it, aligning with its vibe. When in nature, consciousness is abundant: spirit, the thing in itself, the glory of the divine presence, the great pancake in the sky, all make themselves known.

Kaczynski knew this:

Early in the springtime, when the winter’s snow was melted off enough to make it possible, I would take long rambles over the hills, enjoying the new physical freedom made possible by the fact that I no longer had to wear snowshoes, and coming home with a load of fresh, young wild vegetables such as wild onions, dandelions, bitterroot, and Lomatium, with a grouse or two—killed illegally, I’ll admit. Working on my garden early in the morning. Hunting snowshoe rabbits in the winter. Times spent at my hidden shack during the winter. Certain places where I camped out during spring, summer, or autumn. Autumn stews of deer meat with potatoes and other vegetables from my garden. Any number of occasions when I just sat or lay still doing nothing, not even thinking much, just soaking in the peace.

…

In living close to nature, one discovers that happiness does not consist in maximizing pleasure. It consists in tranquility. Once you have enjoyed tranquility long enough, you acquire actually an aversion to the thought of any very strong pleasure—excessive pleasure would disrupt your tranquility.

Finally, one learns that boredom is a disease of civilization. It seems to me that what boredom mostly is is that people have to keep themselves entertained or occupied, because if they aren’t, then certain anxieties, frustrations, discontents, and so forth, start coming to the surface, and it makes them uncomfortable. Boredom is almost nonexistent once you’ve become adapted to life in the woods. If you don’t have any work that needs to be done, you can sit for hours at a time just doing nothing, just listening to the birds or the wind or the silence, watching the shadows move as the sun travels, or simply looking at familiar objects. And you don’t get bored. You’re just at peace.5

Tara finds us a sleep spot using her now well-honed technique, refined over a period of about twenty months, applied almost every day because we need to find a new place to sleep almost every night. She cross references Apple Maps, OS Maps, Park4Nite and Google Street View to locate a suitable place and then tries it on for size against her feminine intuition. It’s a magical divining method that has never failed.

We like remote locations, often small car parks, lay-bys or tracks, situated in natural surroundings. Unfortunately, there are many spoiled places. Things that spoil a sleep spot include: vehicle height barriers, parking charges, people who discard wet wipes, vapes, McDonalds packaging, and Costa cups out of the car window; poorly equipped camper van folk who make rubbish bins overflow, shit under bushes, and empty their chemical toilets by the side of the road; noisy teenagers; campfire remains; fouled toilet tissue; and places heavily populated by dog walkers where the smell of piss prevails and little green bags full of shit are scattered hither and thither.

Thankfully, this spot is a good one: a National Trust car park in the Brecon Beacons at the foot of Pen y Fan, surrounded by sparse woodland, beside some abandoned concrete foundations put there by the military, which still uses the mountain as part of the selection process for the UK’s Special Forces. The large raised solid beds (not officially designated as parking spaces) are just the right size for the van and I manoeuvre on to one for the night.

Through the trees and up the track I can just make out the rise of the mountain, the highest peak in South Wales at two-thousand-nine-hundred-and-seven feet. The two parts of its name mean variously top, head, peak, summit, crest, beacon, hill and mountain. These words tumble together in a lovely Welsh way to give us Pen y Fan which means something like The Mountain's Peak or The Top of the Summit.

It offers a steadying presence as we sleep.

Tuesday 18th February

Foot of Pen y Fan, Brecon Beacons, Wales

At first light there is birdsong and the glow of a dying fire in the sky, which gives way to watery Welsh sunshine.

There’s a big birch polypore razor-strop mushroom down the slope behind the van, growing out of a dead tree trunk. It looks to me like the pronounced snout of a sea cow. In days gone by a strip would be cut from the underside, left to dry and then stuck to a piece of flat wood, used by barbers to give the final finish to the edge of their cut throat razors.

It’s a cold sunny day and we decide to attempt Pen y Fan. Armed with cheese, crackers, apples, and a flask of tea, we set off. Our seven-year-old Red struggles as the path climbs but pushes on through tears. It is steep and it takes a while to find a rhythm, especially at the beginning. After an hour, at the second false peak, we stop at a large flat rock, spread out the rations, and drink piping hot tea with cold hands.

Thor and Oak, the eldest two, want to attempt the peak and Tara is interested, while me, Red, and five-year-old North are satisfied and want to head back down, so we pack up and go our separate ways.

Some hours later, Tara and the boys return to tell their tale. When they left us they guessed that they were at the halfway point. But they underestimated and had to cover a fair few miles to get anywhere near the summit. At the final ascent, the last hundred feet was covered in ice, and there was some doubt they’d be able to climb the frosty path but they managed to dig in and clamber up on all fours. All three are shattered.

Wednesday 19th February

Foot of Pen y Fan, Brecon Beacons, Wales

The drizzle descends in the night. It’s cold and grey in the morning. I’m up and writing from five o’clock. Everyone else sleeps till eleven. The mountaineering has taken its toll.

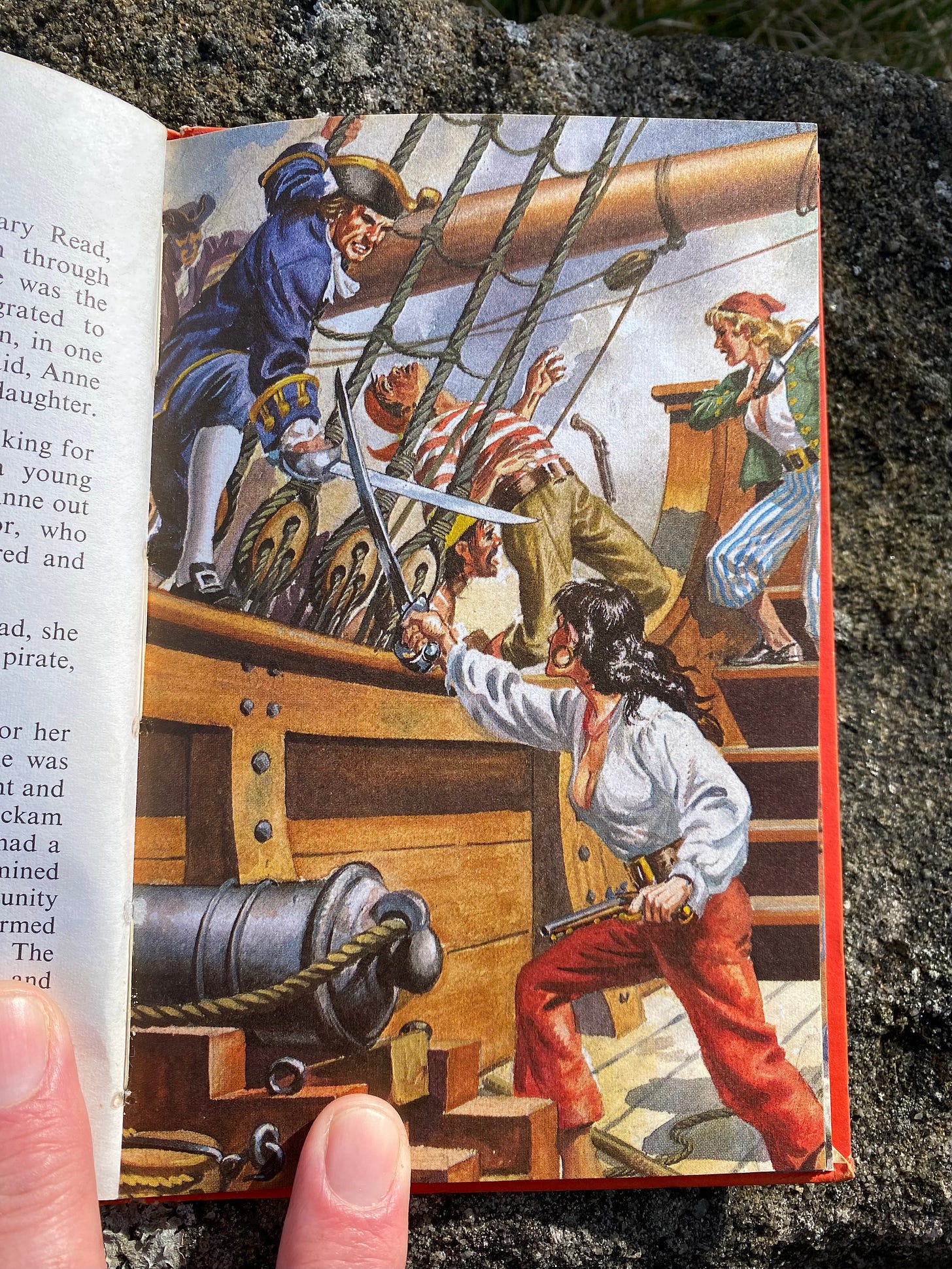

We have breakfast at midday and the mood is subdued. Nobody ventures too far. The children occupy themselves: playing in the woods, reading, knitting. After reading A Ladybird Book about Pirates, Oak whittles a cutlass for his little brother. I notice that all the illustrated pirate women seem to have ample bosoms that want to burst out of their blouses.

There is no-one around today, the weather being more inclement. The mountain is shrouded in dark cloud. Every now and then the breeze picks up, drawing my attention to the circling crow, the hanging catkins. I watch a string of ponies bowing their heads to tear up grass. While they chew, they watch me. I watch them. There is stillness. Something understood.

Stand still. The trees ahead and bushes beside you

Are not lost. Wherever you are is called Here,

And you must treat it as a powerful stranger,

Must ask permission to know it and be known.

The forest breathes. Listen. It answers,

I have made this place around you.

If you leave it, you may come back again, saying Here.

No two trees are the same to Raven.

No two branches are the same to Wren.

If what a tree or a bush does is lost on you,

You are surely lost. Stand still. The forest knows

Where you are. You must let it find you.6

Thursday 20th February

Foot of Pen y Fan, Brecon Beacons, Wales

Mild, grey, damp, dripping.

Last night something was scuttling on the roof while we slept. It didn’t sound like a bird. What it sounded like to me was four little feet and a long tail. I know this sound because when we lived in an old Victorian house we once had an uninvited guest who would scuttle up the interior space between the walls, climb the central heating pipes and then hop up the stairs to our bedroom in the attic where it would gnaw the wooden uprights of the bed and anything else it could get its teeth into. Once while I was sleeping, to my incredulity and horror, it nipped my toe. There is nothing like the close proximity of a wild rat to break the delusion of the civility of man and bring us back to our savage selves. I was haunted by that rat and I wanted its death. Eventually after a night spent chasing and battling it throughout the house we cornered and captured it and I drove three miles away to release it in the woods.

Here in the wild the relationship is different. We all belong here in this wooded copse at the foot of the mountain. I can’t protest its presence, whatever it is. Outside, I shine my head torch at the roof but there is no sign of movement.

In the morning after breakfast Oak makes a sling to fire rocks farther and harder. He has been inspired by the book he is reading, a title from Michelle Paver’s Gods and Warriors series. Obtaining instruction from Primitive Technology he makes his own sling out of paracord. I watch him fire off the first few shots, swinging it rapidly around his head before releasing the stone into the trees.

It’s starting to rain heavily. Time to leave this precious place in the middle of nowhere and go back to the urban sprawl to pick up supplies. The gate down the bottom of the exit track is closed and there is a quad bike blocking the road. An old farmer dressed head to toe in green waterproofs, carrying a crook, comes over, walking with a limp. I wind down the window.

‘Can you give us ten or fifteen minutes? If so go back a bit please.’

‘Sure.’

We reverse back up the track to wait and watch.

I recall seeing two quad bikes racing past just before we left, heading up to the lowlands at the foot of the mountain and wonder if they are part of the same operation.

Soon the string of ponies gallops down the road from the lefthand side as the rain pours down. They look wild and wet as they rush past. The positioning of the farmer, his men, and his vehicles, suddenly makes sense as the animals are steered effortlessly into a waiting paddock with a covered shelter and fresh hay. Gates are shut, others opened, and the old man makes his way over to release us. I ask him if it all went to plan. In a strong Welsh brogue he tells me they needed to get the ponies in off the mountain because the weather was looking rough. Then he urges us onward with a subtle command.

Friday 21st February

Afon Llia, Brecon Beacons, Wales

Good, solid, biblical, Welsh rain.

The landscape: majestic, dignified, is nevertheless sombre and full of sorrow. I can hear David Lloyd’s grave and noble voice lamenting his Little Welsh Home. The mountains, valleys, and streams hold suffering. Sadness is in spate, flowing fast through the riffles and runs of the rain-swollen Afon Llia beside us.

Red helps me make coffee while the others slumber, hiding in bed from the wild, wet, grey day. I give Tara her coffee and a morning hug. She is unreceptive and I notice I experience rejection and dejection which is out of proportion. Something inside starts shifting and all of a sudden I can feel myself slipping away.

Once again for the thousandth time the cracks open up and the emotions pour through: fear, anger, sadness. In a heartbeat I have given up and descended. A black cloud wraps around me and I withdraw.

This is familiar and unbelievably tedious. I have been here too many times. I am fully aware when it happens, I can see it unfolding. Tara has done nothing wrong. She didn’t respond to the hug. It matters not. I’m offering the hug unconditionally. I’m not giving it in order to get anything back. I’m giving it to say I’m here, with love.

If we men can love our women unconditionally, without emotional attachment or reaction, and bear the burden of the selfish, violent, destructive mistakes of generations of men before us, humanity might make it.

If we can be powerful loving men in the face of the feminine storm, then women, children, wildlife, trees, plants, animals, and all the earth will be saved, because we will have restored our true power, that of love, as opposed to dominion.

High stakes then, and it all starts with me, in this moment of pain, where I have offered love and it has been disregarded. All I need to do is keep loving and not succumb to the dark insecure masculine, the frantic, furious, spurned, adolescent boy-man.

Both pathways are alive within me in that pivotal moment and yet, as the ocean of emotional madness rises, I can only watch in horror as it overwhelms me, and I’m not putting up much of a fight.

I have one-hundred-and-one techniques and strategies to draw on, after years of searching, and yet, when it comes to the moment of truth, or the moment of love, I fall short.

I can’t do unconditional love, I can’t give without attachment to an outcome, because I’m broken, and my brokenness, combined with the brokenness of all my fellow men, is the fuel that feeds the human firestorm that has laid waste to the earth and will eventually incinerate everything it touches, until the only thing left to burn is ourselves.

The moment-to-moment choices of eight-billion individual people combine to create the broken world we see around us and I have no power over them. My power lies in taking responsibility for my self and choosing love.

As I choose the opposite: destruction, I enter into despair. I am just immensely bored with my self. I go outside in the miserable rain and walk upstream to sit on a ledge by the river. The dirty brown water races toward me on the bend and then claws at me in a frothing rage as it sweeps past.

Saturday 22nd February

Black Mountain Quarries, Mountain Road, Brecon Beacons, Wales

The Black Mountain, the westernmost range of the Brecon Beacons, is lit up by occasional shafts of sunlight, shining through gaps in the cloud.

Below me, the Mountain Road seeks a path through the peaks, using curve and camber to find its way.

Yesterday, after driving through Neath Port Talbot in torrential rain we saw four felled speed cameras on the mountain road, cut at the base with angle grinder and toppled to the ground. All hail the Welsh BladeRunners hitting back at the authoritarian surveillance system. The peasants are revolting.

I am standing on an old lime kiln, a red kite soars overhead. The kiln is built up out of stone quarried from the slopes. Men have sought the lime contained in the rocks on these high passes for centuries. In the twelfth century they would journey up and dig pits before gathering the limestone rocks from the mountain to stack at the bottom and cover in gorse ferns and timber. A large fire would be set, lit, and sealed with earth to create the high temperatures needed to generate the lime. When the fire had done its work these clamp kiln pits were opened and the lime collected, to be spread on the land where it neutralised acidity and increased yields. In Medieval times it was a modest affair, arable land receiving lime every nine years and grassland every eighteen. But the history of western man is one of ever increasing demand and exploitation and the practice became more widespread, developed and intensive.

In later years many farmers bought what they needed from the newly organised quarries. In 1882 a twenty-two-year-old worker called David Davies was sent by his uncle to collect lime from the workings I am standing on today. He had a long day ahead of him to climb the track up the mountain, fetch the lime, exchange it for coal at the railway station in the valley, then return back to the hills with the coal to receive anther load of lime as payment. He hitched his horse and wagon at dawn. It would be the last time.

By the end of the day David had worked his mare hard and the cart was fully loaded with his payment of lime. As he climbed up to head down the mountain for home, his horse bolted. He fell beneath the wheels and was crushed to death.

Some time after the accident a memorial stone was placed at the site. It disappeared in the 1930s and was restored fifty years later after being found abandoned in a gutter. It is a strange totem, incongruous in the landscape, marking the death of one young farm labourer, whose ghost haunts this lonely mountain pass.

Sunday 23rd February

Black Mountain Quarries, Mountain Road, Brecon Beacons, Wales

We drive off the mountain in a deluge and head through wet Welsh towns until we reach Coaltown Coffee in Ammanford. Frequenting smart, hipster-culture cafes to drink expensive coffee is something I gave up in the summer of 2023 when we moved into a van and it’s not something we do as a family either. Today is an exception.

Coaltown’s interior is natty, paired-back, and retro-industrial. It is all very à la mode. This being Wales, there is a distinct lack of pretence and the ambience is relaxed. The coffee is good, as it should be, and I read about Coaltown’s mission to ‘bring back an industry that produces a new form of black gold’ to the former mining town that used to thrive on coal before Thatcher’s wanton, criminal, destruction of so many communities like this one.

It’s a nice idea, they have genuine local heritage, the founder’s great-grandfather worked his whole life in the surrounding collieries, which is why they’ve named their signature coffee blend Black Gold, but somehow I think it will take more than a coffee roastery and cafe to repair the heart of a devastated community. But then what do I know? I’m a miserable cynic. The baristas are busy and there are plenty of customers this morning - may Coaltown prosper.

The wet day segues seamlessly into a wet night, and we cross a ford in the darkness on our way to a sleep spot on the Gower Peninsula. Just before bed me and Thor spy something in the middle of the road: two frogs. The smaller male is clinging to the underbelly of the larger female, who is lying on her back with all four limbs extended and her four-fingered hands splayed. The female attempts to roll over repeatedly, a task made difficult by the male’s persistent embrace. Eventually with a big heave-ho she manages to flip and the male slides deftly on to her back without breaking grip. Clever fellow. She then makes for the side of the road but her progress is painfully slow and after watching one lucky escape as a car wheel passes, we decide to break our rule of no-intervention in nature and scoop up the suitor and his object of desire, placing them out of harm’s way in the undergrowth.

Monday 24th February

Gower Peninsula, Wales

In the early hours we receive a drive-by beep. The vehicle stops and torchlight shines through our windows. This is an unusual incursion. I get out of bed and go outside to handle it, but by the time I have put my coat on, they’ve gone.

There’s a lot of birdsong here, more than I’ve heard so far this year. It’s a dawn chorus. I can make out robins and wrens and I think I can hear a tree creeper or dunnock. All around me the land is green, squelchy, mossy and damp.

There’s a hazel in front of the van, which I identify by its catkins, with help from Roger Phillips.7 Hazel is known as filbert after St Philibert, a long-dead Frankish abbot whose feast day in August falls at around the time when hazel nuts are gathered. This explanation is problematic because the fruit ripens in October. An alternative suggestion is that filbert is a corruption of full beard, a reference to the long husk which almost completely covers the nut.

We get up and drive to Rhosilli Bay where the gods give us warm hazy winter sunshine to balance the chilly breeze. At the bottom of the long path down to the beach Thor suggests making a fire. He selects a spot and gets it done quick smart with help from his siblings who gather driftwood.

We sit by the flames looking out over the sand and sea. Cheese, crackers, gherkins and avocado precede cups of tea and shortbread. Occasionally the rocks in the fire crack and shatter. A song thrush sings, bringing cheer. The sun drops slowly into the water on the horizon and is gathered in before dark by low-lying clouds.

Thank you for reading my work. If you are a Paid Subscriber, I’m grateful and I don’t take you for granted.

If you remain a Free Subscriber do consider dropping me a virtual tenner now and then, via PayPal or Stripe:

If you become a Paid Subscriber the app will give you three choices:

Monthly Subscriber £5

Annual Subscriber £50

Founding Subscriber £250

Black Mountains or Black Mountain: the Black Mountains are a group of hills spread across parts of Powys and Monmouthshire in southeast Wales, and extending across the national border into Herefordshire, England. They are the easternmost of the four mountain ranges of hills that comprise the Brecon Beacons National Park, and are frequently confused with the westernmost, which is known as the Black Mountain. To confuse matters further, there is a peak in the Black Mountains called Black Mountain.

Henry David Thoreau, author of Walden (1854), immersed himself in natural surroundings for a time, living simply in a woodland cabin he built near Walden Pond, Massachusetts, while painter Paul Gaugin sought refuge from western civilisation in Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands which he viewed as a disappearing paradise.

How his work came to be printed in the pages of The Washington Post is another story: Ted Kaczynski tried to escape the system and return to the wild. A gifted mathematician, he took a job at Berkeley to raise money to buy land. Never satisfied with the idea of spending his life as an academic, he abandoned his career in 1969 and went to live in Lincoln, Nebraska, seeking freedom and personal autonomy in a remote cabin which he built by hand in the woods. It had no electricity or running water. The secluded plot of land cost two-thousand-one-hundred dollars which he paid for in cash, going in fifty-fifty with his brother David Kaczynski, who later betrayed him, tipping him off to the FBI at the insistence of his wife Linda Patrik who first suspected him. Ted Kaczynski turned to murderous violence to get his message across and forced The Washington Post to publish his manifesto in exchange for halting his bombing campaign. You might know him as the UNABOMBER. His crimes do not negate the truth of his words.

Industrial Society And Its Future, Ted Kaczynski, The Washington Post (1995).

An Interview with Ted Kaczynski, Blackfoot Valley Dispatch (1999/2001)

Lost by David Wagoner. From Traveling Light: Collected and New Poems (1999).

Trees in Britain, Europe and North America (1978) and Wild Flowers of Britain (1977), both by Roger Phillips.